When I initially began writing this article, I struggled to anchor my words in a way that expressed my voice and lived experience. I don’t have much experience as a climate activist nor have I been involved in organising with environmental collectives. Because of this I omitted any discursive ramblings on the page. I felt ashamed. I felt like a fraud. Who am I to critique a movement I’ve never been engaged with? I could see that environmental spaces are inaccessible and gatekept yet I couldn’t bring myself to challenge that. I believed the narrative pervading these political spaces; that systemic change in movements can only happen from within and screaming on the outside won’t achieve anything. I internalised this and moved further away from my political values.

This is not a unique experience. Environmentalism in student spaces has become highly factionalised and selective in who can get involved. This form of exclusivity perpetuates discrimination and in turn cherry picks those who can provide an economic benefit to campaigns.

Environmental activism, in its current form, is a movement that is predominantly dominated by the privileged class. This is due to the fact that privileged people have the means to access opportunities of engagement. This includes the financial freedom to travel to different places, even being a part of organisations, whether they are volunteer groups or university collectives. Despite their attempts to be inclusive in language, it is fundamentally resistant to working class interests. It has been swept with theories of ecological responsibilities, often blaming the economically disadvantaged for being a part of the climate change problem. Commonly antagonising those who do not reduce their carbon footprint, it fails to appeal to people who struggle to make ends meet. As disadvantaged groups are disproportionately more affected by climate change, we need to rethink and challenge how we approach our engagement in this movement.

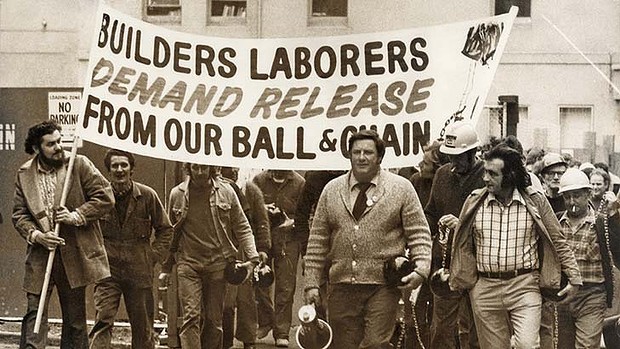

We need to ensure that we do not disenfranchise economically disadvantaged people by gatekeeping. The working class not only are the majority of society, they have leverage over the capitalist system. If we go on strike, the operations of businesses will fall. As we’ve seen recently with transport strikes, the comradity and unity of industrial action is the greatest source of power we have to challenge neoliberalism. It’s this type of action that catches the attention of those who have the political capital to change things. We have strength in this.

It is imperative that the environmental policies we recommend recognises the interrelation between economic development and climate change. The economically disadvantaged are predisposed to experience the worst effects of climate change as their financial conditions make it difficult for them to survive in a capitalistic society. Countering the effects of climate change can only happen through the help of the working class. We need to transform the vehicles that society functions on, and therefore it is vital to consult with the economically disadvantaged in decisions. Appealing to the needs of low income communities – rather than shaming other people’s lifestyle choices – is what we need to dismantle a system that destroys the environment.

When organising, we must ensure that no social group is disadvantaged and excluded. Consulting with marginalised communities is vital to not further compound their disadvantage. We also need to take into account that some of our environmental policies do not take into account the social impacts, or capacities for the public to engage within. The burden then falls on those with lower incomes who consequently feel more disenfranchised.

Perpetuating exclusivity in the movement is fundamentally serving the needs of capitalism. This system benefits from the exploitation of workers, so to tackle our ecological challenges we must challenge who we are fighting for. By ignoring the needs and strengths of the working class we are doing the movement a disservice. It is also not revolutionary to exclude class struggle from your environmental activism. It becomes what Chico Mendes refers to as “gardening.”